Inset Image: Grandad, Stanley Lucas on board one of the many ships he sailed on during his Merchant Navy career

If you could sit on this bench and speak with anyone – dead or alive – who would it be? It’s an often-asked question. For me, the answer is simple. My Grandad, Stanley Lucas.

My Grandad

When I was a child, Grandad was just Grandad. He and Nana visited us every Saturday bringing pocket money and lollies. In the school holidays, my siblings and I would go for sleepovers and they’d give us lemonade spiders (lemonade with a big spoonful of ice cream, for the uninitiated). I remember Grandad teaching me Morse code.

I wish I’d had deeper conversations, asked more questions. It wasn’t until I was older that I had a better understanding of Grandad’s life, especially what he went through during World War II. His experiences helped shape, or perhaps revealed his character, values and virtues.

Grandad, a Liverpudlian, joined the British Merchant Navy in 1934, at the age of 21. He was a radio officer who spent a lot of his life at sea, with voyages often lasting six to nine months.

World War II

During the war, he’d go, along with the other ship’s officers, to top-secret briefings near the waterfront in Liverpool before setting off across the Atlantic to America to load up with cargo essential for the war effort and supplies to feed the country. Tom Hanks’ movie Greyhound gives us a glimpse into what life may have been like during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Convoys of merchant and naval vessels would form near the mouth of the Mersey River, in the Irish Sea and then sail southwards, around the bottom of Ireland and into the Atlantic Ocean. Once there, they were open to attack from the German U boats. It was not a job for the faint-hearted.

According to his service record, Grandad worked on 11 voyages during the six years of the war. This included serving on two ships, torpedoed, and sunk by enemy submarines.

The Titan

The Titan was attacked by a German U boat in the early hours of the morning on 4th September 1940 in the North Atlantic, 250 miles north-west of Ireland. The U boat was under the command of the highly decorated Günther Prien, who became known as the “Red Baron of the Sea” because of his “success” in downing Allied ships.

My uncle said Grandad told him, that he always put his life jacket on the moment a convoy started sailing and it stayed on until he arrived in the US or Canada. He advised new junior crew members to do the same but often the advice fell on deaf ears. Speaking about this incident, Grandad, on hearing the first explosion, said to his junior, “Go and get your life jacket on!”. But the new man was so scared he didn’t know what to do. Following another explosion, Grandad yelled at him to get moving. He knew there was no time to waste.

As the Senior Wireless Officer, Grandad needed to get to the radio room and ensure an SOS message with the coordinates of their location was sent. Lives depended on it.

Six crew members died in that attack. Grandad and the others were rescued and arrived back on land in Scotland five days later.

SS Eumaeus

History repeated itself (well almost) on his very next assignment. The Eumaeus was transporting troops when it was hit by a torpedo fired by an Italian submarine around 6.00 am on 14th January 1941, 118 miles west of Cape Sierra Leone. The submarine then surfaced, and rounds of gunfire rained upon the ship from the deck guns.

There is a harrowing account in an Imperial War Museum oral history recorded by a survivor, George Thomas Cook Alder (reel 2), who speaks of the casualties they tried to save before jumping from the ship into shark-infested waters.

There are varying accounts of the final number that died in this attack, ranging from 23 to 32. The tally included Grandad’s fellow wireless operator, who was killed when the radio shack was taken out by the gunfire. Grandad had been sitting in that seat only an hour or two before the attack.

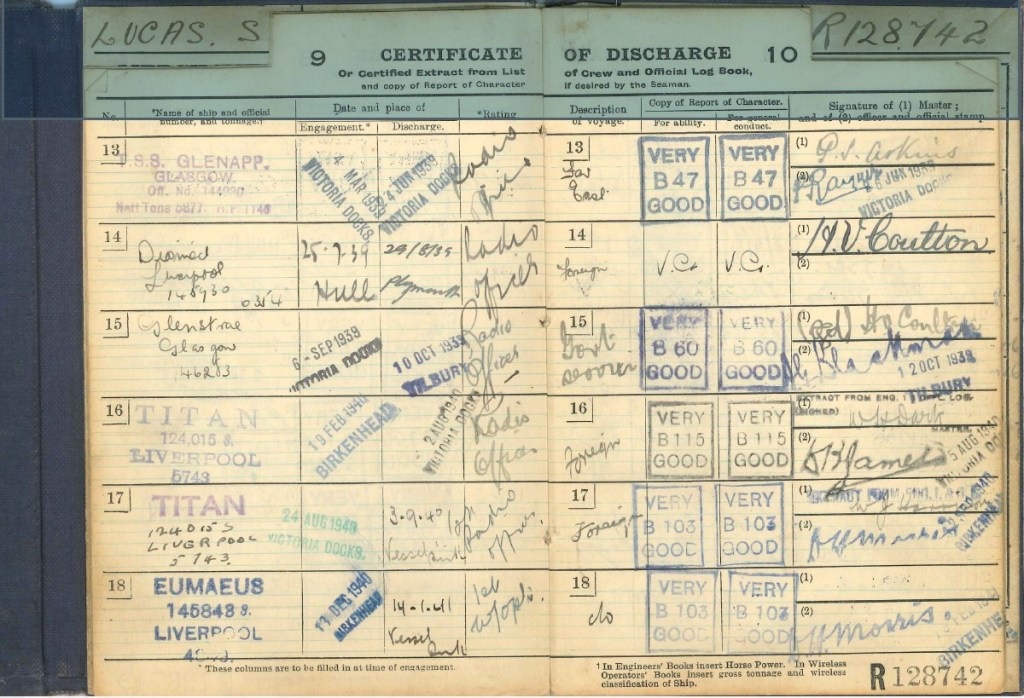

Image: The pages of Grandad’s Merchant Navy Certificate of Discharge Book that show these two ships. In the discharge column, you can see “vessel sunk”

On dry land

Grandad told stories of some dock workers stealing petrol from the lifeboat motors and food from the survival rations. There was a ship that was needed for the war effort and when the boat-builders working on it came back after the weekend, someone had stolen the propeller as it was made of brass and was valuable. Of course, not all dockers were involved, but he despised those who ran black market operations, stealing goods that he and his fellow seamen were risking their lives to bring to the country.

Like other merchant seamen, Grandad was awarded a medal for his part in the Battle of the Atlantic, which is regarded as the longest single theatre of the war, but he threw it in the River Mersey because the same medal was given to the dockers for loading and unloading the ships. He said that they hadn’t put their lives at risk in the same way, and some of them were of questionable character. That said, there would have been many dedicated workers amongst them and the docks, like other parts of Liverpool, were heavily bombed during the war.

Values and virtues

When I think of Grandad and what he went through, three words come to mind:

- Courage

- Resilience

- Integrity

He would never have called himself a hero, but he and all those who served their countries, in whatever capacity, deserve recognition and respect.

Thank you Grandad for all you did for your family, and your country.

Final words

“Courage is the greatest of all virtues, because if you haven’t courage, you may not have an opportunity to use any of the others.” – Samuel Johnson

During the Battle of the Atlantic, the Allies lost more than 72,000 lives; 3,500 merchant ships; and 175 warships.

P.S.

After I’d completed this blog, we received an exciting parcel from England. During Covid, my sister started the process of applying for a replacement medal for our Grandad – the one he threw in the River Mersey. As it happened, he’d been awarded five medals:

- War Medal (1939 – 1945)

- 1939 – 1945 Star

- Atlantic Star

- Pacific Star

- Italy Star

Image: Grandad’s Medals

P.P.S.

I now know that the top secret location in Liverpool that Grandad went to before the Atlantic convoys was Western Approaches – Combined Headquarters, Derby House, Rumford Street, Liverpool.

This historical underground war bunker is now open to the public, and my sister and I were able to visit it in May 2025 as part of our “Following in the Footsteps of our Ancestors” travel adventure. It was quite an emotional experience.

Images: Photographs taken during our May 2025 visit to the Western Approaches in Liverpool

Note: This article was also published in the Liverpool Family Historian – Liverpool and South West Lancashire Family History Society – June 2025

Leave a comment